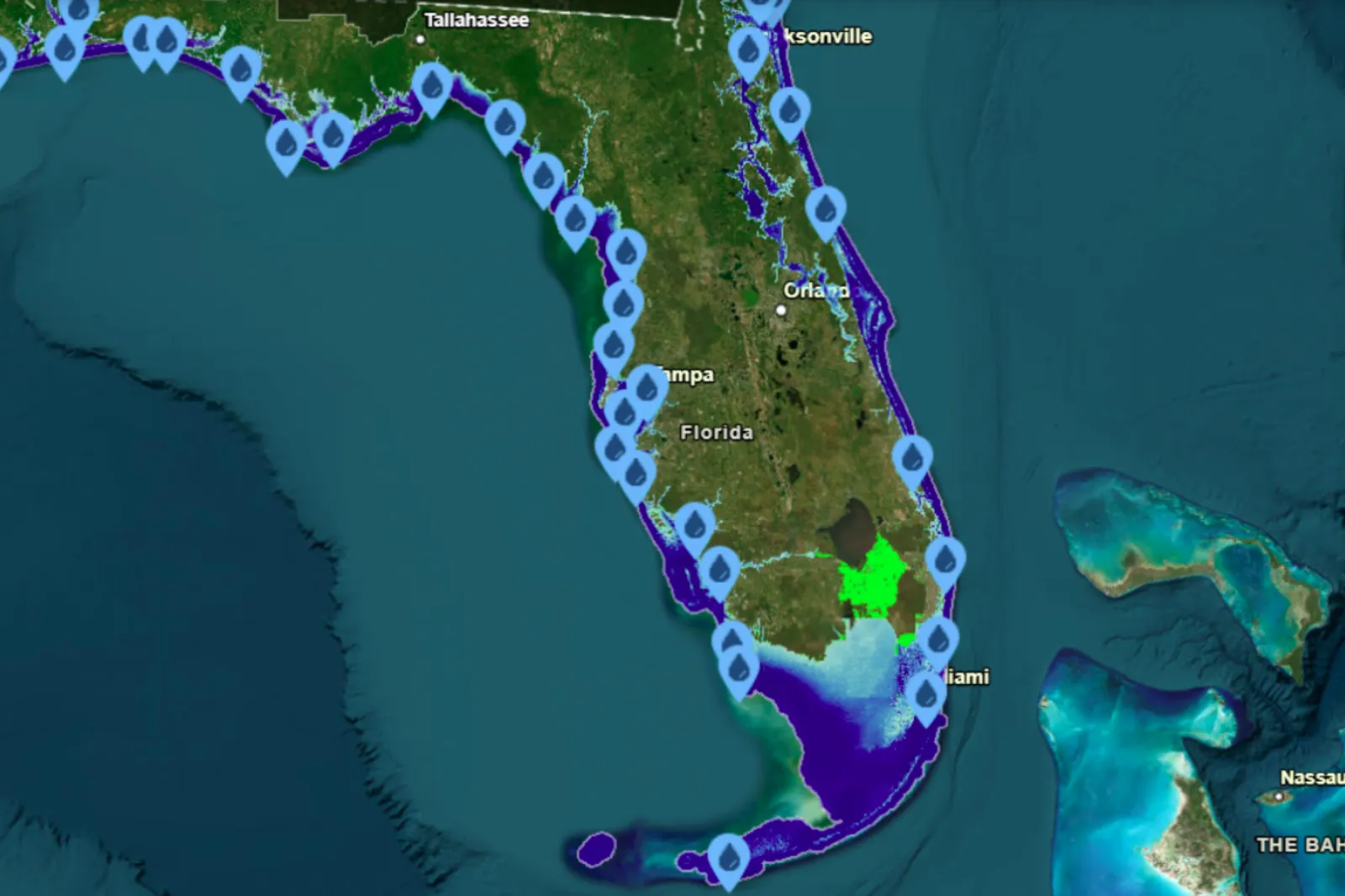

Florida’s shoreline could look radically different if sea levels rise to certain heights, according to a projection map from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The map illustrates which parts of the state would be underwater if sea level rose by 10 feet — a scenario experts say could be possible in the future.

A 10-foot rise (just under 3 meters) is “quite low this century,” William Butler, a professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Florida State University, told Newsweek. But he said a rise of 2 to 3 meters is “not out of the question in the next century,” and becomes more likely without major cuts to greenhouse gas emissions.

“Given the limited progress we seem to be making on that front, we are heading in the wrong direction,” he added.

Why It Matters

Sea levels rise for multiple reasons, including warming temperatures driven by greenhouse gas emissions and the expansion of ocean water as glaciers and ice caps melt.

Butler also warned that even if countries moved quickly to reduce emissions, there could still be “potentially centuries of continued sea level rise,” because some amount of increase is already locked in by current greenhouse gas concentrations.

“In some ways, the question we should be asking is, how much can we slow this process and how much time does that buy us to get ready for several meters of sea level rise,” he said. “Rather than asking ‘how high’, we might need to be asking ‘when?’”

Which Cities and Beaches in Florida Would Be Affected?

Based on NOAA’s map, Florida would be among the states most heavily impacted by a 10-foot sea-level rise, with large stretches of coastline and many well-known beaches disappearing underwater.

Beaches that could be affected include Butler Beach, Flagler Beach, Daytona Beach, New Smyrna Beach, Cocoa Beach, Satellite Beach, Bethune Beach, Jensen Beach, Sunny Isles Beach, Miami Beach, Holmes Beach, Barefoot Beach, Fort Myers Beach, Horseshoe Beach, Keaton Beach — along with many others.

Major cities and coastal communities could also face extensive flooding, including Jacksonville, Port Orange, Melbourne, Port St. Lucie, Fort Lauderdale, Hollywood, Naples, Venice, Sarasota, Tarpon Springs, Crystal River, Cedar Key, Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Panama City.

In South Florida, substantial land area — including several wildlife reserves — would be inundated under this scenario. Areas listed as vulnerable include Everglades National Park, Biscayne National Park, the Southern Glades Wildlife and Environmental Area, Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Key West National Wildlife Refuge, National Key Deer Refuge, and Pine Island National Wildlife Refuge, among others. Pine Island itself would also be submerged.

What a 10-Foot Rise Could Mean on the Ground

Butler described a 10-foot sea-level rise as “devastating” for U.S. coastal cities — especially across the Gulf Coast, the Southeast, and the Mid-Atlantic — and said places like New York and Boston would also be affected. He added that Miami could become “an archipelago.”

He warned that critical infrastructure would be pushed beyond its limits. Stormwater systems, water supply, and sewer networks could “fail.” Roads would be submerged, bridge access could be cut off at ramps, transit systems could flood, and some high-rise buildings might be left standing like isolated columns surrounded by water. As properties lose value and tax bases shrink, local budgets could strain — or collapse — making adaptation projects harder to fund.

Large-scale displacement would also be likely, Butler said, potentially triggering “millions” of moves away from vulnerable coastal areas as people relocate for jobs, family ties, or whatever stability they can find.

He emphasized that many effects are already visible today. “Low-lying areas are already flooding more frequently, even on sunny days,” he said.

Insurance markets, he added, are reacting quickly, with many companies “abandoning the most at-risk markets like Florida and Louisiana.”

Another growing risk is saltwater intrusion into freshwater wells. Butler said salt levels are already high enough in some areas to force wells to shut down.

“This is all happening now, with less than 1 foot of sea level rise in the last 120 years,” he said. “10 feet would make what we’re dealing with now look like a walk in the park even though it is costing billions just to adapt to the current context.”

What Should Be Done?

Butler said planning needs to be the starting point — mapping scenarios, identifying vulnerabilities, deciding what areas to defend, and determining where future development should be avoided.

From there, engineered approaches can help reduce near-term risks. He pointed to strategies such as retrofitting and floodproofing infrastructure and buildings, elevating land (as Miami Beach has done), and using pumps and valves to block seawater and clear stormwater.

At the same time, Butler argued that reducing greenhouse gas emissions remains essential. He said the U.S. could lead by supporting investment in alternative energy, reforestation, carbon capture, and other efforts that reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Such measures won’t stop sea-level rise in the coming centuries, he said — but they can slow it and reduce the eventual peak, lowering long-term impacts on coastal cities.

One major obstacle, Butler added, is funding. A broader federal push to support and expand these efforts could speed up adaptation and preparedness.