The disappearance of a Chicago candy heiress has puzzled investigators for decades — and remains one of the city’s most enduring mysteries.

Helen Brach vanished on February 17, 1977, in a case that would grow to include burned diaries, claims of psychic writings, an empty grave, forged checks, a meat grinder, and even a pink Cadillac. Yet despite years of investigation and speculation, one crucial element has never been found: Helen Brach’s body.

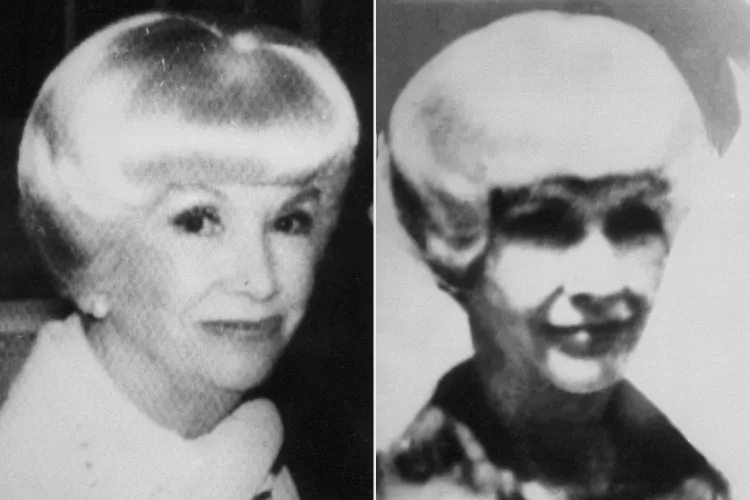

Brach had married into the Brach candy dynasty and inherited a sizable fortune after the death of her husband, Frank Brach. By most accounts, she was a private, reserved woman, though also eccentric. She was well known for owning multiple luxury cars painted in the company’s signature colors — pink and lavender.

At age 65, Brach traveled to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, for a doctor’s appointment on the day she disappeared. Investigators later said she took a taxi from the clinic to the local airport. Her longtime housekeeper, Jack Matlick, claimed he picked her up later that day at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport.

According to Matlick, he spent much of the following weekend with Brach at her 18-room mansion in Glenview, an affluent Chicago suburb. He said the last time he saw her was when he drove her back to O’Hare for a Monday morning flight to her condominium in Florida.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(809x0:811x2):format(webp)/helen-brach-1-121525-660e7eb503cc4e66b3223f88e54dc341.jpg)

Brach never arrived.

Friends who tried calling her Glenview home that weekend told investigators she never came to the phone. Instead, Matlick reportedly offered inconsistent explanations about her whereabouts.

His behavior soon raised additional concerns. Investigators noted that Matlick thoroughly cleaned the maid’s room at Brach’s mansion, had one of her Cadillacs washed inside and out, and ordered a meat-grinder attachment from a Chicago department store. He also cashed six checks totaling $13,000 that were purportedly written by Brach. Her accountant later noticed the signatures were not hers. Matlick claimed her wrist had been injured by the lid of a heavy trunk, affecting her handwriting, but experts concluded the signatures were neither Brach’s nor Matlick’s — deepening the mystery.

Matlick had worked for Brach and her husband for roughly 20 years. After Frank Brach died in 1970, Matlick became Helen’s closest aide and confidant. Despite this, nearly two weeks passed before he reported her missing.

Though Matlick reportedly failed multiple lie detector tests, he was not the only person scrutinized during the investigation.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(1099x0:1101x2):format(webp)/brachs-candy-corn-121525-9157a11ac7544edfa6e886c4e4f4d2af.jpg)

Brach’s brother, Charles Vorhees, admitted that he and Matlick had burned his sister’s diaries and her so-called “automatic writings” — pages she created by tightly holding a pencil and allowing what she believed were psychic forces to guide her hand. Vorhees later said he believed Helen would not have wanted anyone to read them. At the time, he stood to benefit from a $500,000 trust connected to her estate.

Another figure who drew attention was horse dealer Richard Bailey. Brach had previously purchased approximately $300,000 worth of thoroughbred horses from Bailey — animals authorities later said were worth far less.

In the 1990s, federal prosecutors accused Bailey and his associates of running racketeering schemes that targeted wealthy clients unfamiliar with the horse industry. According to court filings, prospective buyers were lured to stables through advertisements, then evaluated for wealth using confidential financial information. Those deemed affluent were persuaded to invest large sums in horses that were allegedly overvalued or nearly worthless.

The indictment also included an explosive allegation: that Bailey had solicited Brach’s murder as part of a broader conspiracy involving insurance fraud and the killing of dozens of horses.

Bailey was ultimately convicted of fraud and racketeering, including defrauding Brach, and in 1994 he was sentenced to 30 years in prison. While he was never convicted of her murder, the judge said the length of the sentence reflected Bailey’s alleged role in a conspiracy tied to her disappearance. He was released in 2019 and died in 2023 at age 93.

Brach was declared legally dead in May 1984. By then, her fortune had reportedly grown to more than $40 million. Her will directed $500,000 to Charles Vorhees and a $50,000 annuity to Matlick — though Matlick later relinquished his claim. Much of the remaining estate went to animal welfare charities.

Matlick died in February 2011 at age 79 in a Pennsylvania nursing home. Though he was never charged, some law enforcement officials publicly stated after his death that they believed he was responsible for Brach’s disappearance.

Former ATF agent Jim DeLorto later said Matlick carried critical secrets to his grave, adding that he likely knew what happened to Helen Brach and what became of her body.

Because her remains were never recovered, Brach’s official gravesite — a private family plot beside her husband and her dogs — remains empty. In 1990, authorities exhumed a body believed at the time to possibly be hers, but it was later determined not to be.

Nearly half a century later, the disappearance of Helen Brach remains unsolved.