When it was time to clean the house, Kaitlin Reeve says she wasn’t only reaching for the hoover — she was reaching for cocaine.

The 39-year-old mother of three, from Surrey, says she lived with addiction for around 20 years, spending anywhere from £20 to £200 a day on cocaine and cannabis. She described running on little sleep while trying to keep family life moving.

“Most days, I was getting the kids ready for school on very little or no sleep,” she said. “I was going to work, picking them up from school, getting them to bed, then at night I would get back to what I was doing.

“I needed a line to do the cleaning. It was the only way I could muster up the energy to do it. It was as normal as a cup of tea. I did do it at work fairly often as well.”

Ms Reeve said she first tried cocaine at 16 while working in London. She had started drinking alcohol in primary school, began smoking cigarettes at 11, and used cannabis by 15.

At the height of her addiction, she said she was taking between half a gram and three grams of cocaine a day. She also described going to extreme lengths to conceal it, including hiding drugs behind light fittings.

‘I wasn’t present, even when I was there’

Despite holding down jobs — including work as an estate agent and barmaid — and caring for her children, Ms Reeve said she felt emotionally detached.

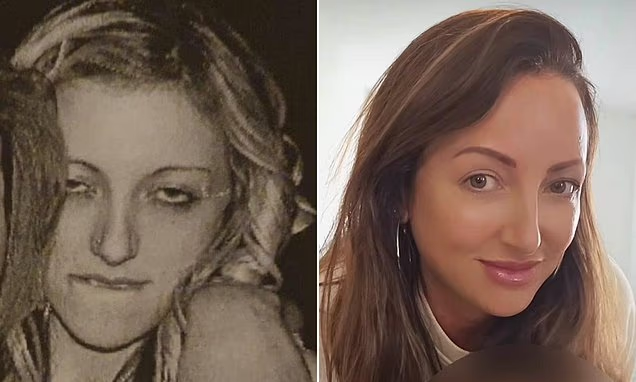

Looking back, she said it’s clear to her that she often appeared to be coping on the outside. “When I look back at photos, I can see I still took them on days out and did arts and crafts with them, but I wasn’t present,” she said.

“Other people would say, ‘Kaitlin does this with her kids and she’s great at this’ — but inside I was dying. I was very depressed. I found day-to-day life very stressful. I was often lazy as a parent when I look back.”

She has an 18-year-old daughter and two sons, aged 14 and five.

‘Glamour’ and the spiral back into the cycle

Ms Reeve said her early experiences with cocaine were tied to the social scene she encountered as a teenager in London, including working as a club promoter in Kensington.

“The first time I tried it was in a penthouse in Kensington and I felt really glamorous,” she said. “When I started doing cocaine, I felt grown up.”

She said the drug made her feel able to “hold her own” in environments where she was surrounded by celebrities and high-society nightlife.

But over time, she said, the habit grew and she began going out alone rather than staying at home. When she became pregnant with her daughter at 20, she cut down, but after a relationship ended a few years later, she said she slipped back into the same pattern.

“It all crept back in and it was time to go back out partying,” she said.

After the births of her sons, Ms Reeve said hiding her drug use became harder — and the psychological effects began to intensify.

“Towards 2013 and 2014, I was getting paranoid, hearing things, thinking people were watching me all the time,” she said. “Eventually, I decided I wanted a better life for my children, so I moved away from London to get away from it all — and I did — but it crept back in.”

She added that everyday life felt “depressing and scary,” and that drinking and drugs became the only coping mechanism she knew.

A wider surge in cocaine use — and the health risks

Britain is believed to consume around 117 tonnes of cocaine a year, according to the UK’s National Crime Agency, amid a sharp rise in use.

People often describe a short-lived “buzz” or surge of confidence from the stimulant, but as the effects fade quickly, users may take more to recreate the initial high — raising the risk of psychological dependence.

Long-term use has been linked to serious mental health problems, including paranoia and insomnia.

The UK also has one of the highest rates of cocaine use globally, with around one in 40 adults — about 2.7% of the population — reporting use, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Snorting cocaine can also damage the nose. The drug causes strong constriction of nasal blood vessels, sometimes described medically as vasculitis. For some people this leads to congestion and irritation, but with heavier or repeated use, reduced blood supply can damage tissue and, in severe cases, contribute to perforations of the nasal septum.

‘I lost my sanity, my dignity, my self-worth’

Ms Reeve said the financial cost of addiction was huge — and that she suspects she could have afforded a house with what she spent over the years.

“I never lost my kids or my house or any of that stuff,” she said. “But I lost my sanity, my dignity, my self-worth.”

She described deteriorating health, including a moment that frightened her. “I remember one time looking in the mirror and my face had gone grey and my lips were blue from sniffing,” she said. “I still went back and did another one.”

Even while struggling, she said she continued to work, though jobs often didn’t last.

“I used to think, ‘Why don’t people like me?’ but then I was turning up hungover and on no sleep,” she said. “Jobs would fizzle out but I always had a job. One would end and I would go for the next one.”

The moment she decided to stop

Ms Reeve said she became sober three years ago after what she described as a “moment of clarity” while smoking a joint in her garden.

“One day, I was sitting in the garden smoking a joint and I literally can’t describe what happened,” she said. “I was enlightened and I thought, ‘You’re going to kill yourself and this is your opportunity to turn this around.’”

She said fear kept her from seeking help sooner — especially fear of losing her children.

“To be honest, I had wanted to stop for years but I was so scared that if I asked for help I’d lose my children,” she said. “All I ever wanted to be was a good mum so the thought of losing my kids was awful for them just as much as me.

“I’m grateful I didn’t lose my children but I’m even more grateful they didn’t lose me.”

A few days later, she attended a recovery group meeting — a step she said felt terrifying, but ultimately changed everything.

“I walked in all dressed up because I wanted to look like I wasn’t that bad,” she said. “And I said, ‘I’m Ms Reeve and I’m an addict,’ and I surprised myself.”

She said it was the first time she truly believed change was possible after seeing others who had been through similar experiences.

‘Recovery has given me freedom’

Now, Ms Reeve says she shares her experiences on social media, is training to become a therapist, and supports others through a 12-step fellowship.

“Recovery has given me freedom,” she said. “I don’t have a big house or fancy cars, but I have peace. I have a brilliant relationship with my children.

“If I can help another woman and her children not to go through what some other children have to go through, then me sharing my story is worth it.”

She added: “I used to look at my kids every day and break inside, but they were the reason I kept going.”