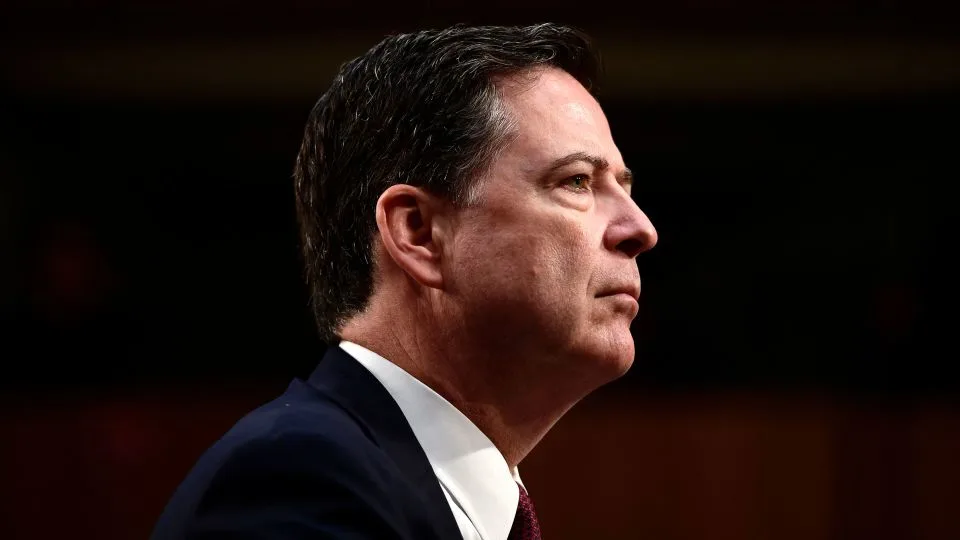

James Comey’s longtime friend and former attorney Daniel Richman is suing the Justice Department over evidence it collected from him years ago and later used in the now-dismissed criminal case against the former FBI director — a move that could complicate the Trump administration’s efforts to bring new charges.

The Justice Department obtained data from Richman’s online accounts, iPhone, iPad and an external hard drive in 2019 and 2020. That trove of material had become a growing point of contention in the criminal case against Comey in Northern Virginia before the case was thrown out last month.

Richman, a Columbia University law professor, is now asking a federal court in Washington, D.C., to issue an emergency order barring the Justice Department from accessing his files and to hold a hearing on whether his constitutional rights were violated.

He argues that the government’s continued access to his data shows a “callous disregard” for his Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures.

“There is no lawful basis for the government to retain any images of Professor Richman’s computer, whether stored on the Hard Drive or elsewhere,” the lawsuit states. “The government’s conduct has deprived Professor Richman of his constitutional rights, and the injury to Professor Richman will continue if his property is not returned.”

Richman’s new filing raises the possibility that a judge could more deeply examine alleged prosecutorial missteps that were never fully aired in Comey’s case before its dismissal, or potentially restrict evidence prosecutors may seek to use if they attempt to rework charges against Comey stemming from his 2020 congressional testimony.

DC District Court Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly, a veteran judge in national security matters and an appointee of President Bill Clinton, has not yet responded to the lawsuit, according to the court docket. The Justice Department also has not filed a response. The original search warrant records — which authorized access to Richman’s email, iCloud and other accounts and data — remain under seal in the DC District Court.

In many respects, Richman’s suit picks up where Comey’s criminal case ended.

Comey’s legal team had been gaining traction with arguments that the Justice Department and FBI mishandled evidence and misused material in their grand jury presentation before securing an indictment in late September. President Donald Trump had publicly called for Comey’s prosecution, and the indictment arrived just days before the statute of limitations was set to expire.

Comey pleaded not guilty before the charges were dismissed. The indictment accused him of misleading Congress in 2020 about his interactions with Richman, and court records indicate that grand jurors in Alexandria, Virginia, were shown material drawn from Richman’s files.

Last month, a federal magistrate judge in Virginia sharply criticized the Justice Department’s reliance on the years-old Richman evidence before the 2024 grand jury, saying prosecutors had displayed a “cavalier attitude towards a basic tenet of the Fourth Amendment.” The judge wrote that the government effectively allowed itself to “rummage through all of the information seized from Mr. Richman, and apparently, in the government’s eyes, to do so again anytime they chose.”

The original search warrants were tied to a national defense leak investigation known as Arctic Haze, which, Magistrate Judge William Fitzpatrick noted, did not authorize investigators to seize evidence related to the eventual charges against Comey — namely, allegations that he lied to Congress in 2020.

Fitzpatrick also pointed out that the material taken from Richman sat unused for years and that the Justice Department did not obtain new warrants to revisit it when building the Comey case. He further faulted prosecutors for failing to use proper procedures to screen out potentially privileged attorney–client communications, especially given Richman’s role as one of Comey’s lawyers. Comey’s team said they had never been given access to the seized material before he was indicted.

The Arctic Haze investigation never produced criminal charges, and Richman has never been accused of a crime.

“Although the Arctic Haze investigation decisively concluded in 2021, the government to this day indefensibly retains Professor Richman’s Files,” his attorneys wrote in the new lawsuit filed in DC District Court. They argue that the Justice Department’s handling of the evidence “exemplifies precisely the governmental abuse against which the Fourth Amendment was designed to protect.”

Comey’s criminal case came to a sudden end after a separate judge ruled that Trump-backed lawyer Lindsey Halligan — who had been acting as the U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of Virginia and solely presented the case to the grand jury in late September — lacked the legal authority to serve in that role at the time.

Because the case was dismissed before Comey’s lawyers could obtain grand jury records or formally contest the evidence, their inquiry into Halligan’s conduct and the investigators’ methods was largely cut short. The Justice Department has said it intends to appeal the ruling that invalidated Halligan’s actions, though that appeal has not yet been filed. Prosecutors could first return to the grand jury in an attempt to secure a new indictment.