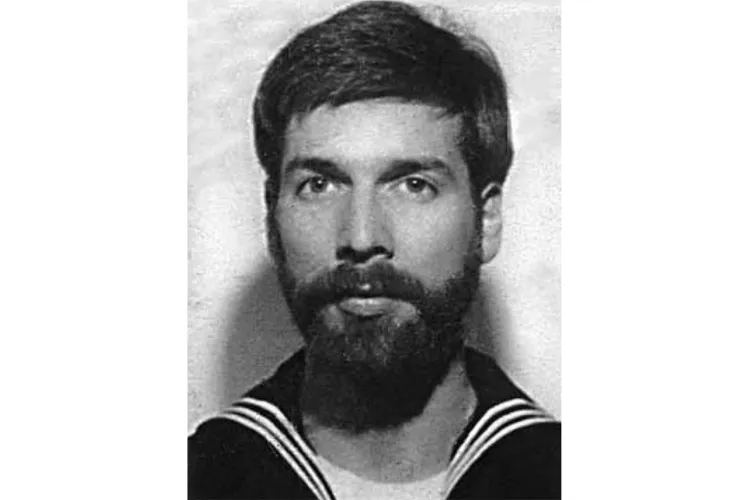

When a U.S. Navy photoanalyst disappeared from the United States in 1986, it would take two years before he resurfaced — and when he did, he was on the other side of the world, living in Russia under a different identity.

A 1989 report described how American officials had long suspected Glenn Michael Souther of betraying his country. But it was an obituary published in Moscow that offered the clearest picture of what he was alleged to have done for the Soviets before his death at 32.

In that obituary, Souther was identified as Mikhail Orlov. Soviet officials praised him as a high-value spy who delivered “precious” secrets — including U.S. plans for a nuclear-war scenario involving the Soviet Union. According to the report, Souther’s work allegedly earned him the rank of major in the KGB. Yet despite the accolades, his life in the U.S.S.R. appeared to be unraveling. On June 22, he died by suicide after inhaling exhaust fumes from his car.

KGB chief Vladimir Kryuchkov was quoted as saying Souther’s “nervous system could not stand the pressure” of life in the Soviet Union.

Back in the United States, many who knew Souther struggled to reconcile those claims with the person they remembered. Friends from his years at Virginia’s Old Dominion University recalled someone impulsive and attention-grabbing — a regular party presence who rarely seemed interested in global politics or espionage.

Souther was born on Jan. 30, 1957, and raised in a working-class neighborhood in Indiana. His father worked as an office manager for the company that produced Wonder Bread, and his mother worked as a secretary. He was described as an average student and a track runner.

“Glenn was a nice, straightforward guy, like the rest of us,” former track teammate Tom Rasch said at the time, adding that Souther didn’t come across as politically engaged or focused on international affairs.

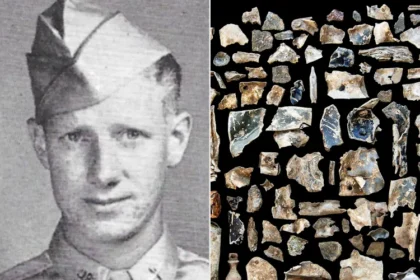

After high school, Souther enlisted in the Navy. He served aboard the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz from 1976 to 1978, then transferred to the Sixth Fleet in Italy. During that period, he married and became a father. Investigators believed he may have been recruited by the KGB while stationed overseas.

In 1982, Souther was assigned to Maryland. He was later honorably discharged, then joined the Naval Reserve in Norfolk, where he worked analyzing satellite photographs — a role that allegedly gave him access to highly classified military material.

Around that same time, Souther began studying Russian at Old Dominion University, where his reputation as a party-loving student grew quickly.

“He was the guy at parties who always put on a lamp shade,” Barbara Fahey — whose husband, John, served as Souther’s adviser in Russian studies — recalled.

But others described moments that felt unsettling. One fellow student said Souther once called seeking Russian-language tutoring — then, about an hour after the phone conversation, arrived at her door speaking “fluent” Russian and talking erratically. During the introduction, she said he brought up a rape allegation that had been made against him the year before. The student claimed Souther “obviously was crazy.” (The outcome of the allegation was unclear.)

Even some faculty members found him hard to assess. One professor reportedly called him one of his “worst students.” Yet Leonid Mihalap, a Russian professor at the university, said Souther’s grasp of the language was so strong it raised suspicions.

Mihalap pointed to a term paper Souther wrote on Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky — a paper he described as so polished it made him wonder whether a native Russian had written it.

At one point, Souther’s estranged wife reportedly told Navy officials she suspected him of spying for the U.S.S.R., but an investigation found no proof. Years later, authorities revisited her warning.

After graduating, Souther quietly relocated to Moscow. He did not publicly resurface until 1988, when he acknowledged defecting and began criticizing U.S. nuclear arms policies and intelligence activities. Reports later claimed he married a Russian woman and had another child, though little was publicly known about his daily life there before his death in 1989.

Some who knew him believed resentment may have played a role — including speculation that he felt humiliated after being rejected from Naval Officer Candidate School. Fahey was quoted as saying, “I think he decided to defect because he wasn’t making it here. So he said, ‘Well, I’ll show you!’”