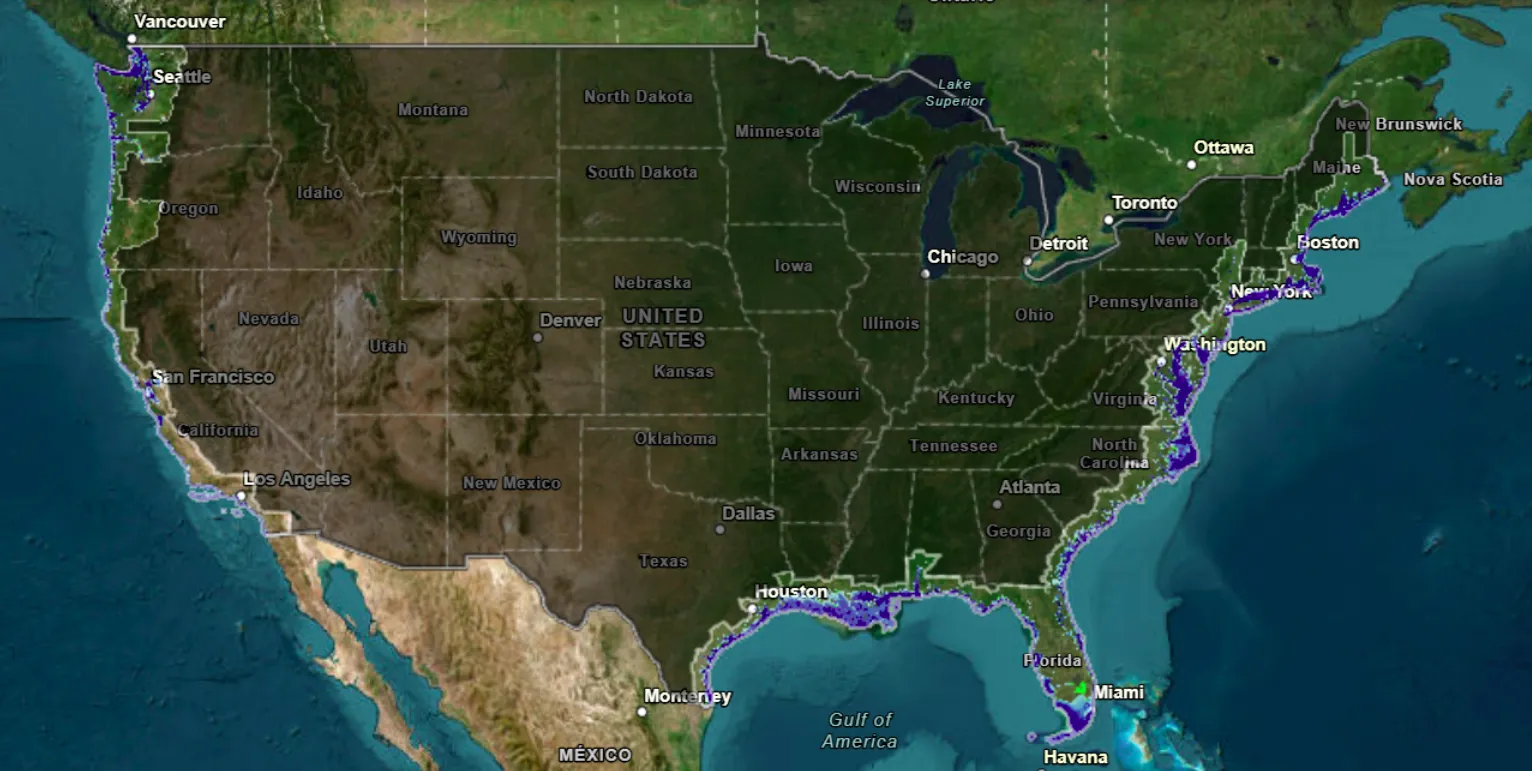

A NOAA sea level map suggests that a 10-foot rise would inundate wide stretches of the U.S. coastline, threatening neighborhoods in many major coastal cities.

Coastal geologist Randall Parkinson, a professor at Florida International University, called a 10-foot rise “catastrophic,” warning it would reshape shorelines and disrupt essential systems far beyond the immediate waterfront.

Why it matters

Rising seas don’t just mean more coastal flooding. They can also endanger facilities that store or handle sewage, trash, oil, gas, and other hazardous materials—raising the risk of spills, contamination, and long-term public health impacts.

Research has identified thousands of hazard-related sites that could be exposed to coastal flooding by 2100. The same work suggests many locations may face flood risk much sooner—potentially by 2050—and that low-income communities, communities of color, and other marginalized groups may be disproportionately affected.

What the map indicates

Across the West Coast, the NOAA projection shows parts of Washington impacted, with areas of cities such as Seattle, Aberdeen, and Port Townsend partially submerged. Sections of Oregon’s coastline also show extensive flooding.

In California, coastal flooding becomes widespread in low-lying areas, including places such as Crescent City and portions near major metro areas like San Francisco and Oakland, as well as parts of Long Beach and San Diego.

On the East Coast, large areas of Maine’s coastline appear vulnerable, along with parts of Massachusetts, including areas around Boston, Gloucester, Salem, and Quincy. Rhode Island also shows significant exposure, including cities such as Warwick and Newport.

In New York City, the map suggests partial inundation across multiple boroughs, including parts of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island.

Further south, Atlantic City, New Jersey is shown as highly exposed, along with Ocean City and other nearby coastal communities. Flood risk on the map also extends through Maryland toward Baltimore, and into Virginia, including areas around Newport News and Virginia Beach.

In the Carolinas, the map highlights major impacts in North Carolina, including cities such as New Bern, Greenville, and Jacksonville. In South Carolina, coastal areas around Charleston are also shown as at risk.

Georgia’s coast appears heavily affected as well, with flooding projected in cities such as Georgetown, Darien, and Brunswick. Florida shows some of the most dramatic changes, with exposure indicated across many coastal cities and communities including Jacksonville, Melbourne, Port St. Lucie, Fort Lauderdale, Hollywood, Naples, Venice, Sarasota, Tampa, and St. Petersburg—along with numerous beach areas.

Along the Gulf Coast, the map suggests that while New Orleans itself may remain relatively safer in this scenario, much of the surrounding region could be submerged.

In Texas, projected impacts include coastal areas around Texas City, Port Lavaca, Rockport, Corpus Christi, and Portland.

What a 10-foot rise could break first

A rise of this scale would threaten far more than buildings. Parkinson warned that critical underground infrastructure could fail early, including stormwater and sewer systems that depend on gravity to move water toward treatment facilities.

He also emphasized the role of groundwater. As sea level rises, the groundwater table can rise too—meaning flooding can begin farther inland even before seawater overtops the shoreline. That can lead to chronic “nuisance” flooding or even permanent freshwater flooding in areas not typically considered coastal.

Saltwater intrusion is another concern. Parkinson described it as a process that can push salinity well inland, potentially affecting shallow drinking-water wells and irrigation wells. It can also accelerate corrosion, damaging structural elements in buildings and infrastructure such as roads and culverts.

How likely is a 10-foot rise?

Parkinson said he considers a 7-foot rise by 2100 “very likely,” and suggested that 10 feet above present levels would follow—roughly two decades later.

He pointed to several drivers of sea level rise, including thermal expansion (as warmer seawater takes up more volume) and the addition of water from melting land glaciers. He noted that meltwater input is expected to accelerate toward the end of the century.

Reducing carbon dioxide emissions remains the most important action for slowing future warming and limiting long-term impacts, he said—while also stressing that carbon dioxide persists in the atmosphere for centuries, meaning some change is already locked in even if emissions stopped immediately.

What coastal planning may need to become

Parkinson argued that coastal planning will need to shift away from “protect and defend” approaches and toward managed migration—gradually moving people and assets away from frequently flooded, high-risk areas.

In this approach, the most exposed zones could be converted into natural buffer areas, helping protect more inland communities from sea level rise and storm surge.