Even modest amounts of walking may help slow brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease, according to new research. The study also points to a specific range of daily steps where the benefit appears strongest.

Researchers at Mass General Brigham tracked nearly 300 adults ages 50 to 90 who had no dementia symptoms when the study started. Over more than nine years, participants’ daily step counts were recorded, and periodic brain scans measured amyloid-beta and tau — proteins closely linked to Alzheimer’s. Elevated levels of these proteins can indicate very early disease activity, years before noticeable memory problems.

Participants also took annual cognitive tests to monitor changes in thinking and memory. The researchers paid special attention to people who already had higher amyloid levels at baseline, since that group carries a greater risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s.

Among those higher-risk participants, walking just 3,000 to 5,000 steps per day (about 1.5 to 2 miles) was associated with delaying cognitive decline by roughly three years compared with people who were less active. The most pronounced benefit appeared in participants who averaged 5,000 to 7,500 steps daily, with decline delayed by about seven years.

The study, partly funded by the National Institutes of Health, was published in Nature Medicine. In addition to cognitive outcomes, the team found that higher step counts were linked to slower accumulation of tau in the brain, suggesting physical activity may influence one of the most damaging processes in Alzheimer’s.

Interestingly, participants who began the study with low amyloid levels didn’t show major differences in cognitive outcomes based on how much they walked. The largest effects were concentrated in those already showing early Alzheimer’s-related changes.

The results also challenge the common 10,000-step target. Benefits in this study leveled off around 7,500 steps per day, indicating that for many older adults, moving from very low activity to a few thousand steps daily may provide meaningful long-term protection.

Senior author Jasmeer Chhatwal, M.D., Ph.D., said the findings may help explain why some people on an Alzheimer’s trajectory decline more slowly than others. Lifestyle factors, he noted, appear to affect the earliest disease stages, suggesting that early changes in daily habits could delay the appearance of cognitive symptoms.

Because the study is observational, it can’t prove that walking directly caused the slower decline. People who are more active might also have other protective habits — such as healthier diets or stronger social engagement — that contribute to better outcomes. The researchers also cautioned that the volunteer group was mostly healthy and well-educated, so results may not fully represent the broader population.

Experts not involved in the work called the findings promising, while emphasizing that exercise is only one part of a bigger lifestyle picture. Prior research suggests that physical activity works best alongside other factors like nutritious eating, mental stimulation, and social connection.

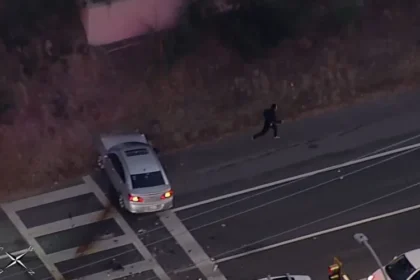

For older adults who want to add more walking safely, common guidance includes planning routes in advance, letting someone know your schedule, carrying identification and a charged phone, wearing supportive shoes, choosing well-lit paths, staying alert to traffic, and using crosswalks. Small, steady increases can add up over time.

First author Wai-Ying Wendy Yau, M.D., said the takeaway is simple: even a few thousand steps a day could matter, and consistent movement may help build lasting changes that support brain health.