The Justice Department has moved aggressively to undermine the federal judge overseeing the case against former FBI director James B. Comey, criticizing his language from the bench and trying to walk back a striking admission prosecutors have repeated in recent days.

At a contentious hearing Wednesday in federal court in Alexandria, Virginia, prosecutors acknowledged that the final version of Comey’s indictment was never presented to a fully constituted grand jury — a procedural gap that could prove fatal to the case.

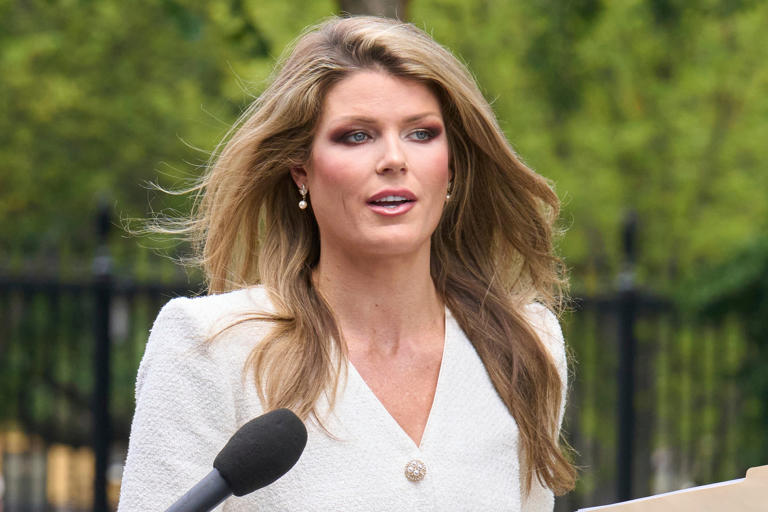

Afterward, interim U.S. attorney Lindsey Halligan and a Justice Department spokesperson launched a public-relations push that drew support from conservative media. But the approach risks antagonizing U.S. District Judge Michael S. Nachmanoff at a critical moment, as he considers whether the case is an unconstitutional vindictive prosecution driven by officials acting outside ethical boundaries.

“What happens when you allege that the judge is personally attacking you? … You’re at risk of poking the bear,” said Tim Belevetz, a former Eastern District of Virginia prosecutor who supervised fraud and public corruption cases. “The best practice, frankly, is to attack your opponent’s position, and not even attack your opponent personally, but attack their position.”

President Donald Trump fired Comey as FBI director in 2017 and has criticized him since, first urging prosecution in 2018. This year, Trump removed interim U.S. attorney Erik S. Siebert — who had declined to pursue charges — and replaced him with Halligan, a former White House aide with no prosecutorial background. Days before the filing deadline, Trump publicly pressed Attorney General Pam Bondi to prosecute Comey and two others.

Halligan obtained a two-count indictment accusing Comey of false testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2020 — specifically, denying he authorized leaks to the news media — and of obstructing the same proceeding. Comey has pleaded not guilty.

Before trial, the judge could dismiss the case as vindictive prosecution prohibited by the Constitution. To prevail, Comey must show Halligan acted with “genuine animus” or was influenced by another official with animus such that she served as a “stalking horse,” and that he would not have been prosecuted “except for the animus,” according to legal precedent.

In Wednesday’s hearing, Nachmanoff questioned Comey’s attorney, Michael R. Dreeben, about that standard. “So your view is that Ms. Halligan is a stalking horse or a puppet, for want of a better word, doing the president’s bidding?” the judge asked.

“Well, I don’t want to use language about Ms. Halligan that suggests anything other than she did what she was told to do,” Dreeben replied, adding: “She didn’t have prosecutorial experience, but she took on the job to come to the U.S. attorney’s office and carry out the president’s directive.”

Halligan later said Nachmanoff had attacked her. In a statement to the New York Post, she argued that the judge’s wording was improper. A Justice Department spokesperson posted her statement on X.

“Personal attacks — like Judge Nachmanoff referring to me as a ‘puppet’ — don’t change the facts or the law,” Halligan said. She then cited judicial ethics, saying canons require judges to be “patient, dignified, respectful, and courteous” and to act in ways that promote public confidence in the judiciary’s integrity and impartiality.

Justice Department spokesman Chad Gilmartin echoed the complaint on X, accusing Nachmanoff of an “outrageous and unprofessional personal attack.”

Judges, however, often use synonyms to probe legal arguments. Asked why the term was considered a personal attack rather than a relevant question, Gilmartin said, “There is no case law for the pejorative word ‘puppet,’ which is the precise language this federal judge used in open court.”

Separately, the prosecution is also under pressure over how it finalized Comey’s indictment.

The grand jury rejected an initial indictment containing three counts. All sides agree the panel rejected the first count, a point the foreperson confirmed in open court on Sept. 25.

Halligan’s office then prepared a revised indictment, removing the first count and retaining the two counts grand jurors had approved, and presented that two-count version to the court.

What happened between the initial vote and the filing of the final indictment has become central — and the government’s account has shifted.

Over the past week, Halligan and her prosecutors said at least seven times in court arguments or filings that the full grand jury never saw the final two-count indictment. But after Nachmanoff pressed the issue on Wednesday, the government filed papers offering a different framing.

At the hearing, Nachmanoff asked Assistant U.S. Attorney N. Tyler Lemons: “That new indictment was never presented to the entire grand jury in the grand jury room; is that correct?”

After conferring with Halligan, Lemons said the government viewed the process as involving “only one indictment presented,” arguing the edits merely reflected the jury’s vote and did not amount to a “new indictment.”

Nachmanoff restated his question: “Let me be clear that the second indictment, the operative indictment in this case that Mr. Comey faces, is a document that was never shown to the entire grand jury or presented in the grand jury room; is that correct?”

“Standing here in front of you, your honor, yes, that is my understanding,” Lemons answered.

Halligan had made a similar sworn statement. She said she presented the case once, left the room, and later learned the first count was rejected while the other two were approved.

“I then proceeded to the courtroom for the return of the indictment in front of the magistrate judge,” Halligan said. “During the intermediary time, between concluding my presentation and being notified of the grand jury’s return, I had no interaction whatsoever with any members of the grand jury.”

In a filing Wednesday, prosecutors said a deputy chief directed the grand jury coordinator to remove the rejected count and renumber the remaining ones.

“The grand jury coordinator then returned to the grand jury room and presented the corrected indictment to the grand jury foreperson and the deputy foreperson,” the filing stated.

The next day, Assistant U.S. Attorney Gabriel J. Diaz offered a new interpretation, pointing to the brief exchange when the foreperson received the indictment.

“So you voted on the one that has the two counts?” the magistrate judge asked. “Yes,” the foreperson replied.

“This sworn testimony alone establishes that the grand jury voted on the two-count indictment,” Diaz wrote.

Asked whether the full grand jury reviewed the final indictment, the Justice Department pointed to Diaz’s filing and the foreperson’s response.

Comey’s attorneys argue the case must be dismissed because “the grand jury never approved the operative indictment,” citing the Fifth Amendment and a rule requiring at least 12 jurors to concur.

“But here, at least 12 jurors did not concur in the operative two-count indictment; and the grand jury rejected the only indictment that the government presented to it,” the defense wrote in a filing Friday.